The Cultural Trends of Women in Politics during the Roman Empire

QUESTION: Mr. Armstrong; I assume you would know the answer. Is it true that the women in ancient times were more like Hillary seeking power compared to modern times?

JF

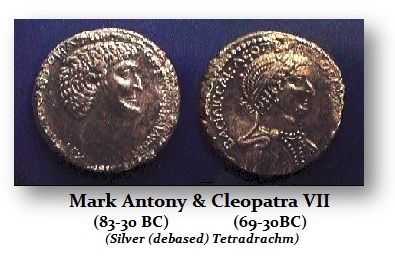

ANSWER: Yes, I have heard this assertion before. It is only partially true. Unquestionably, the first woman of Eastern culture to act politically was none other than Cleopatra VII. She loved Julius Caesar and bore his son in hopes of taking over Rome. When Caesar was assassinated, she fled Rome back to Egypt. She then seduced Marc Antony. That did not end well and Octavian defeated them as it was portrayed as one of the epic love stories which was probably more for political advantages as is the case with Hillary and Bill who now live separately.

However, it was not appropriate for Octavian to boast a victory over a Roman such as Marc Antony, and yet it was also inappropriate to drag a woman through the streets as being conquered. It was not out of the question that Octavian had Cleopatra killed for this difficulty. The coinage he issued avoided proclaiming victory over Antony and Cleopatra personally and simply claimed he defeated Egypt.

There appears to be a cultural difference in history between the Eastern area of the Roman Empire and that of the West. The women in the East historically appear to be much more dominant in politics than in the West, where perhaps the saying originated, “Behind every great man stands a great woman supporting him.” I recommend an old BBC series to watch called “I Claudius.” It was a fantastic series that revolved around the Julio-Claudian family that was really driven by the intrigue of Augustus‘ wife- Liva. The series shows how she killed off the heir of her husband, Augustus, so her son, Tiberius, would become emperor. She was said to have more bodies than Hillary is alleged to have orchestrated. The difference was that Liva did not seek to be emperor, where Hillary stuck with Bill to make a run for president.

There was also Agrippina, Jr., who most likely orchestrated the assassination of Britannicus, the son of Emperor Claudius, so her son would become Emperor Nero. Where Livia’s portrait appears on coinage, it is always in the form of a goddess rather than in her own name. In the case of Agrippina, Jr, she is the first woman to be pictured on Roman coinage in her own name. Here she is pictured with her son Nero facing him as she ruled the empire. Eventually, she was so manipulative that Nero was blamed by the people for the murder of Britannicus. Nero eventually turned against her and had her killed.

There was also Agrippina, Jr., who most likely orchestrated the assassination of Britannicus, the son of Emperor Claudius, so her son would become Emperor Nero. Where Livia’s portrait appears on coinage, it is always in the form of a goddess rather than in her own name. In the case of Agrippina, Jr, she is the first woman to be pictured on Roman coinage in her own name. Here she is pictured with her son Nero facing him as she ruled the empire. Eventually, she was so manipulative that Nero was blamed by the people for the murder of Britannicus. Nero eventually turned against her and had her killed.

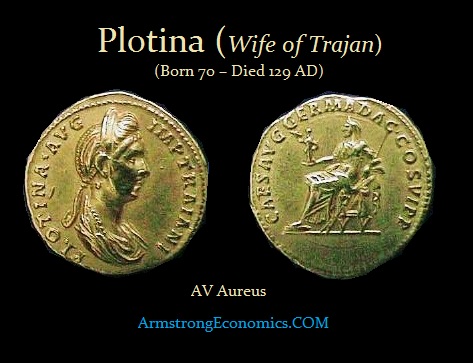

Women seem to have remained behind the throne following Agrippina Jr. certainly in advising but also acting more like a first lady would. The next woman in the middle of a scandal was the wife of Emperor Trajan – Plotina. A letter Trajan was said to have composed on his deathbed appeared in Rome with Plotina’s signature on it, in which he adopted Hadrian naming him successor to the Empire. This raised suspicion that it was crafted by Plotina who was fond of Hadrian.

Women seem to have remained behind the throne following Agrippina Jr. certainly in advising but also acting more like a first lady would. The next woman in the middle of a scandal was the wife of Emperor Trajan – Plotina. A letter Trajan was said to have composed on his deathbed appeared in Rome with Plotina’s signature on it, in which he adopted Hadrian naming him successor to the Empire. This raised suspicion that it was crafted by Plotina who was fond of Hadrian.

We do not really encounter the outright politically dominant women until the late 2nd century and they are from the East. It is not just one woman, but a number of them that began to manipulate politics and take more of an open role. The first is Julia Domna who was the wife of Septimus Severus and the mother of Caracalla.

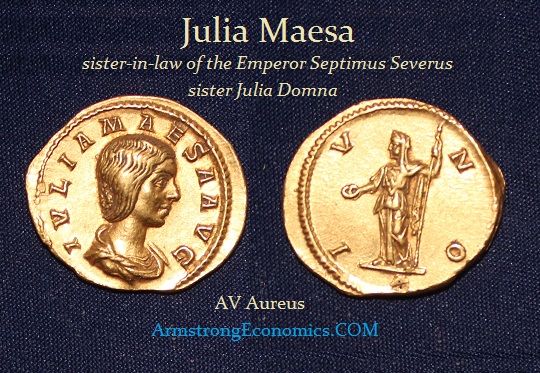

It was the women of Julia Domna’s family that really dominated politics under 235 AD. Julia Maesa was the sister of Julia Domna and sister-in-law of the Emperor Septimus Severus. Julia Maesa bore two daughters, Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea, the mothers of the Emperors Elagabalus and Severus Alexander respectively. Julia lived in Rome with her sister during the reign of Caracalla. Following Caracalla’s assassination and Macrinus’ rise to the throne, Julia was permitted to retire to her home at Emesa in 217 AD. This act of mercy on the part of Macrinus would later prove to be a fatal mistake. Once back in Syria, Julia Maesa masterminded the conspiracy in the provinces that led to the fall of Macrinus and the elevation of her grandson Elagabalus to the throne of the Roman Empire in 218 AD. When Elagabalus was murdered, his mother went with him and they dragged their bodies through the streets of Rome in celebration. Julia Mamaea was the mother of Severus Alexander. She was murdered when her son was assassinated. She was the last of this line of Eastern women to rule.

There was Zenobia, also of the East located in Syria. She led a rebellion and split off the Eastern provinces from Rome. She raised her son to the rank of emperor, but she was the dominant political figure and issued coins proclaiming she was effectively the Empress. Because she was a woman, when she was conquered by Aurelian she was allowed to retire. There was a cultural issue that it did not appear to be appropriate for a man to conquer a woman and execute her.

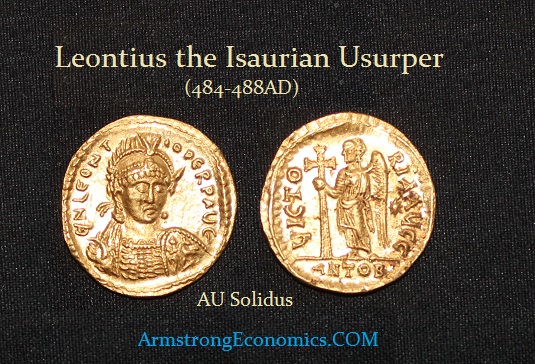

In 479 AD, the emperor Zeno’s mother-in-law, the meddlesome dowager empress Verina, the wife of Leo I, managed to convince her other son-in-law Marcian, son of the late western emperor Anthemius, to a raise a revolt. It collapsed due to the quick reaction of Zeno’s Isaurian general Illus, and Verina’s complicity in both it and in an attempted assassination of Illus was quite plain. She was then given to Illus to be imprisoned in Dalisandus in Isauria. By 484 AD, however, the situation had changed: Illus was reported to be intriguing against the emperor, and not only refused the empress Ariadne’s request that her mother be released, but had the audacity (in Ariadne’s opinion) to avoid being assassinated by her agents (who seem to have been as incompetent as her mother’s had been five years earlier).

Illus withdrew to his native Isauria, and Zeno then sent the patrician Leontius with orders to obtain Verina’s release. The unexpected result of this was that Leontius made peace between Verina and Illus, and after Illus brought her in full regalia to Tarsus, she crowned Leontius emperor on July 19th, 484 AD. She attempted to convince the provincial forces to go over to him by stressing her legitimate right as empress to crown an emperor, but after a very short occupation of Antioch the rebels were tossed out again, and in September were heavily defeated by Zeno’s army under John the Scythian. The survivors fled to the virtually impregnable fortress of Cherris in Isauria where they remained bottled up until their capture and execution in 488 AD (Verina herself had already died in late 484 AD).

Illus withdrew to his native Isauria, and Zeno then sent the patrician Leontius with orders to obtain Verina’s release. The unexpected result of this was that Leontius made peace between Verina and Illus, and after Illus brought her in full regalia to Tarsus, she crowned Leontius emperor on July 19th, 484 AD. She attempted to convince the provincial forces to go over to him by stressing her legitimate right as empress to crown an emperor, but after a very short occupation of Antioch the rebels were tossed out again, and in September were heavily defeated by Zeno’s army under John the Scythian. The survivors fled to the virtually impregnable fortress of Cherris in Isauria where they remained bottled up until their capture and execution in 488 AD (Verina herself had already died in late 484 AD).

Whenever possible, rebels like Leontius and Illus would have wanted their own coinage, both to underscore their legitimacy as rulers, as well as to pay the troops they so desperately needed. The capture of Antioch provided them with a mint, though one which was not accustomed to gold coinage, and they must have immediately begun turning all available gold into coins bearing the name and titles of Leontius as emperor. The fact that the obverse legend is in the dative case, rather than the expected nominative, shows that it was meant to be seen as an acclimation issue.

The dies for Leontius’ solidi were cut with great rapidity by relatively unskilled craftsmen (the legends can be slightly garbled, Greek U’s are used rather than Latin, etc.). Traditionally, Leontius is thought to have only held Antioch for 12 days but it has been suggested by others that the coronation of Leontius took place in March and that his occupation of Antioch lasted two months.

In any event, thanks to Verina, Leontius’ gold coinage is among the rarest of Roman issues. Few coins have survived simply due to the collapse of the rebellion and the demonetization of any usurper’s coinage. It was tradition to recall all the coinage of a usurper and melt them down. There are in fact only four known examples with each struck from a different pair of dies makes the original abundance of the coinage fairly clear. With this number of dies, it implies that the coinage issue could have easily produced 400 lbs of gold coins to pay the troops. The discovery of these coins confirms both the location and the fact that they were culled out of circulation. The coin illustrated here is from a 19th century Levantine hoard of several hundred solidi of Zeno and Leo I, suggesting that the hoarder did not notice the image of the usurper.