Why Was Jesus Crucified?

QUESTION: Mr. Armstrong; You are clearly a Roman scholar. Is it true that the Romans used crucifixion only for political crimes and that the two who were crucified with Jesus were not thieves but rebels? There has been some debate on this subject. I would like to hear your views.

Thank you

WR

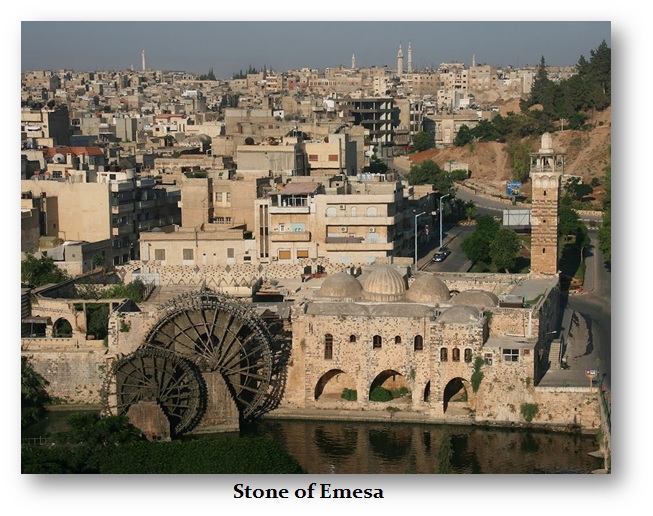

ANSWER: Jesus’ crime was really sedition and not blasphemy. The high priests may have seen this as blasphemy, but Jesus would never have been put to death by the Romans for such a local issue. The Romans practiced freedom of religion. They allowed the provinces that they had conquered to retain their own gods. Even the Roman Emperor Elagabalus (218-222AD) was an heir to the throne being of the Severian House. He had been a priest in Emesa of the sun god, which is the modern city of Homs in Syria today. He worshiped a black meteor that had fallen from the sky and a temple had been built for this stone of god (see above). When Elagabalus became emperor, he carried the Stone of Emesa to Rome and built a temple there. After he was murdered, the Romans respectfully returned the stone to Syria as to not offend any god. As for the Black Stone of Emesa is concerned, it was most likely smashed to pieces when the temple was converted into a Christian church at some point during the 4th Century AD by the Byzantines.

ANSWER: Jesus’ crime was really sedition and not blasphemy. The high priests may have seen this as blasphemy, but Jesus would never have been put to death by the Romans for such a local issue. The Romans practiced freedom of religion. They allowed the provinces that they had conquered to retain their own gods. Even the Roman Emperor Elagabalus (218-222AD) was an heir to the throne being of the Severian House. He had been a priest in Emesa of the sun god, which is the modern city of Homs in Syria today. He worshiped a black meteor that had fallen from the sky and a temple had been built for this stone of god (see above). When Elagabalus became emperor, he carried the Stone of Emesa to Rome and built a temple there. After he was murdered, the Romans respectfully returned the stone to Syria as to not offend any god. As for the Black Stone of Emesa is concerned, it was most likely smashed to pieces when the temple was converted into a Christian church at some point during the 4th Century AD by the Byzantines.

Therefore, the only possible way that Jesus would have been crucified was for a civil crime, not a religious one, and the penalty had to be only for sedition, which is conduct or speech inciting people to rebel against the authority of a state. It is rabble-rousing, incitement to rebel, subversion, troublemaking, but not a religious issue. Therefore, the high Jewish priests took Jesus to the governor and had to make their case that he was inciting a rebellion against Rome by claiming to be King of the Jews. Pilate interrogates Jesus:

“You are a king, then!” said Pilate. Jesus answered, “You say that I am a king. In fact, the reason I was born and came into the world is to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to me.

“What is truth?” retorted Pilate. With this he went out again to the Jews gathered there and said, “I find no basis for a charge against him.”

Rome’s punishment only for a political crime was a crucifixion, which was a public display that was painful, and a visible warning to others. There is no possible way that the two men crucified with Jesus were common thieves. The sentence of crucifixion was only something that Rome could order. The two men who were killed along with Jesus are identified in the Gospel of Nicodemus as Dismas and Gestas.

Luke 23:39-41 says, “One of the criminals who hung there hurled insults at him: ‘Aren’t you the Christ? Save yourself and us!’ But the other criminal rebuked him. ‘Don’t you fear God,’ he said, ‘since you are under the same sentence? We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve. But this man has done nothing wrong.'”

Matthew refers to Barabbas who is released by Pilate in place of Jesus only as a “notorious prisoner” and that would never imply a common thief. Mark and Luke further refer to Barabbas as one involved in a στάσις (stasis, a riot), probably one of the numerous insurrections against the Roman power who had committed murder. The translation as “thieves,” however, the word can also mean “insurgents,” and it is more-likely-than-not that the two were co-conspirators of Barabbas rather than thieves. This is the only possibility that would support the sentence of crucifixion, which was a political weapon used to send a message to those still living: Do not engage in sedition or this will be your fate.

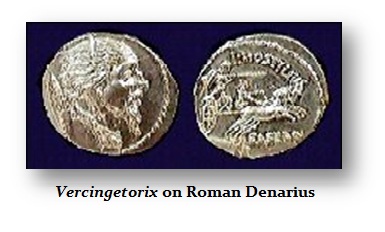

Crucifixion was an execution that was severe and reserved for political crimes, not common thieves. The more common method of execution in the Roman Empire was by strangling. Even the leader of the Gauls, Vercingetorix, who was an adversary was put on display in a triumph of Julius Caesar and then strangled – not crucified. This was simply a captive of a conquered nation or group who had not been under Roman rule and thus did not warrant crucifixion.

Crucifixion was an execution that was severe and reserved for political crimes, not common thieves. The more common method of execution in the Roman Empire was by strangling. Even the leader of the Gauls, Vercingetorix, who was an adversary was put on display in a triumph of Julius Caesar and then strangled – not crucified. This was simply a captive of a conquered nation or group who had not been under Roman rule and thus did not warrant crucifixion.

Spartacus (111-71BC) was a Thracian gladiator who escaped and became a slave leader during the Third Servile War, a major slave uprising against the Roman Republic. Crassus crucified 6,000 of Spartacus’ followers on the road between Rome and Capua pictured here in the 1878 painting by Fyodor Bronnikov. Again, the punishment of crucifixion is employed for rebellion. Even Karl Marx listed Spartacus as one of his heroes and described him as “the most splendid fellow in the whole of ancient history” and a “noble character, real representative of the ancient proletariat”.

Therefore, from a historical perspective of Roman law, Jesus would then have been crucified ONLY as a rebel and not for blasphemy. Giving a choice to the crowd between Jesus and Barabbas would not have been plausible unless they both stood for the same type of offense of sedition. This to me is clear evidence of the political nature of Jesus’s execution and was not merely a local religious issue but was a crime of sedition against the Roman Empire.